What led us to pursue food systems in architecture & urbanism?

‘Architecture is the craft of invisible forces’.

Some years ago, Schmidt Hammer Lassen began reexamining how architecture, design and urban planning firms delivered projects. It seemed unreasonable that a holistic approach to the needs of people, society and ecology was administered in a limited way through certifications in parallel to a project brief.

We found that our industry is educated to treat buildings and urban plans as economic objects with typological and operational requirements. Architects and planners are aware of the instrumental power that shaping space has on behaviour but remain in need of a flexible and context-specific approach that deals with the complexities of ecology, community, health, equity, infrastructure, and collaboration.

Looking to alternatives, we were inspired by the field of ecology, which examined the connections between things. From this perspective, we developed a system we call ‘Living Design’, now used by cities and municipalities, developers, collaborators and ourselves to guide each of our projects from day one. It is a holistic, flexible and context-specific method of revealing needs, connecting them to the design process and guiding a project from strategy to completion.

Our Living Design process begins by assessing hundreds of potential approaches and tailors this to the project context. Using data points, mapping, indicators, and personal engagement, we create a clear picture of potential successful outcomes and a detailed roadmap guiding creative solution finding and collaboration.

Through our process of assessing the needs of projects, communities and cities, we repeatedly came across food as an instrumental factor in the desired outcomes of these projects. Cultural identity, communal interaction, intergenerational connection, health and well-being, resilience, climate, biodiversity and personal agency, amongst other things, are deeply connected to food.

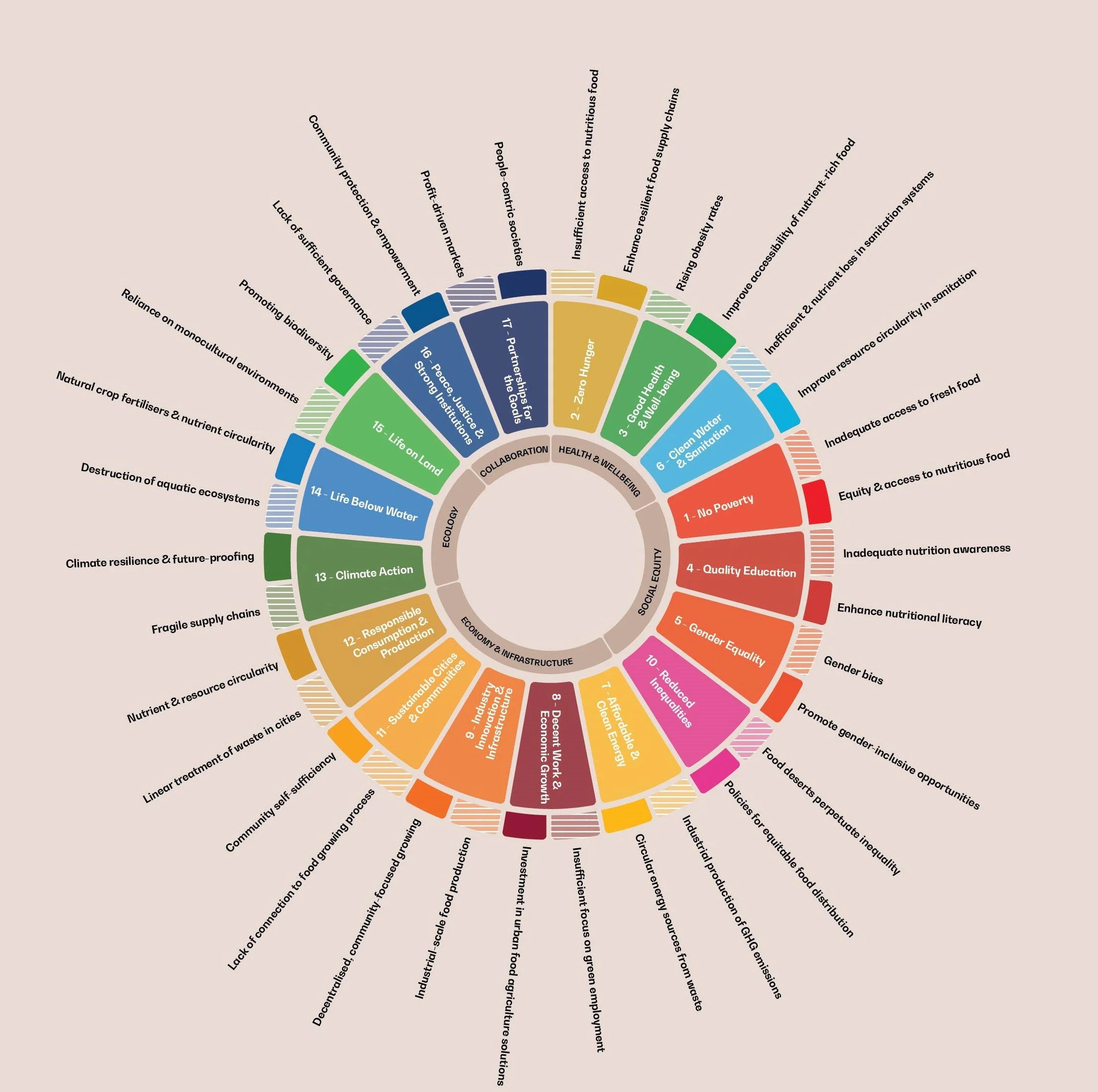

Many cities and municipalities have begun to run gap analyses against the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UNSDGs) to create their own directives for civic improvement. Equity and resilience around food tend to be central themes.

The city and countryside, recast through this lens, reveals an overall blind spot in how we design our buildings, cities and food systems. Beyond the immediate ramifications of our urban landscape, the food production and waste systems the city relies on are understood as the primary cause of ecological destruction facing humanity. Ironically, the same system that keeps us alive threatens our very existence (read Welcome to the Biosphere for a more detailed explanation).

Why, if food systems are so influential in our daily lives, does the design profession largely ignore them in the built environment? If food and nutrient waste remain unconsidered in our architectural work, masterplans and urban framework, we lose the agency to recraft our cities into something more desirable. These invisible forces, tied to food, resilience, health, equity and community, are contingent on our ability to redesign our cities for both personal and common good.

ESSAYS

Enlai Hooi

René Nedergaard

Jette Birkeskov Mogensen

Lene-Maria Toksværd

Ann-Britt Elvin Andersen